The line between scary and creepy is thin in nature. Some creatures are frightening because they can hurt us; others unsettle us simply through appearance or behavior. Today, we’re celebrating some of the most uncanny corners of the animal kingdom — species that make your spine tingle not only because they look otherworldly but because they remind us how wild and strange life on Earth really is. Behind every eerie face or terrifying jaw, there’s also a conservation story worth telling. These may be some of the scariest animals in the world, but they're also some of the most beautiful and fascinating, uniquely adapted to the ecosystems they call home. Here are 13 of the scariest animals in the world:

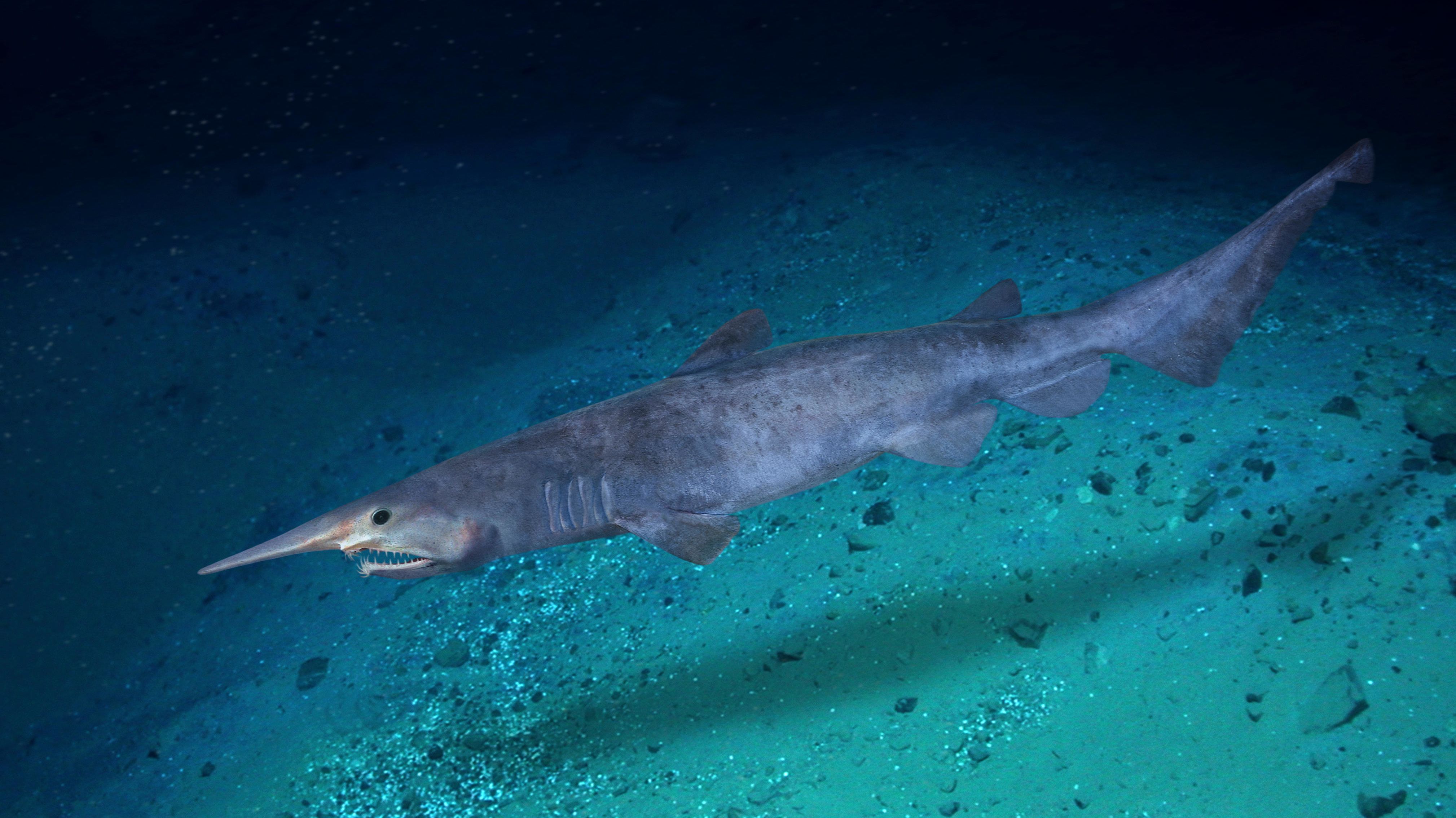

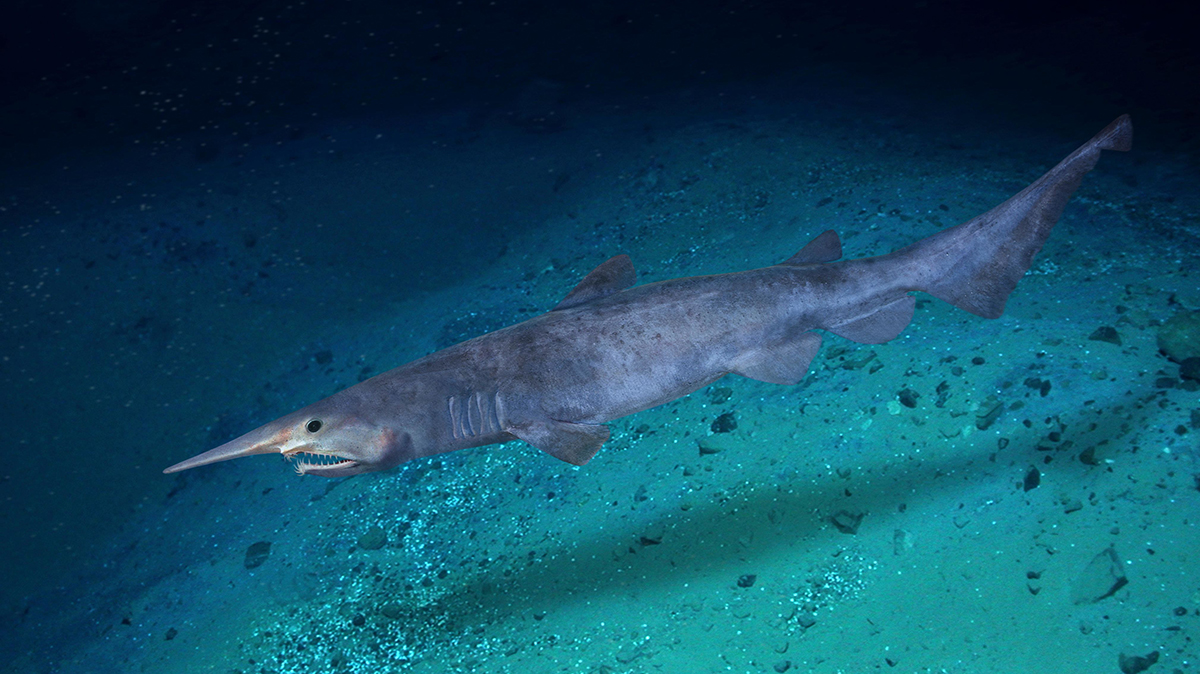

The goblin shark looks like something time forgot — and in a sense, it is. A “living fossil” with a lineage stretching back 100 million years, it patrols the deep ocean with pale, flabby skin and a long blade-like snout. When it attacks, its jaws shoot forward like a spring-loaded trap, snatching fish and squid in an instant.

Despite its monstrous appearance, the goblin shark is harmless to humans and rarely encountered, an elusive relic of an ancient sea. However, the Florida Museum of Natural History notes that they're sometimes caught as a bycatch of deepwater trawls, longlines, and deep-set gill nets. There's still so much left for humans to learn about deep-ocean life, and it's imperative that we protect these under-explored ecosystems.

The Japanese spider crab is a living sea monster. Its legs can stretch more than three meters from tip to tip, making it the world’s largest arthropod. Found off Japan’s Pacific coast, it scours the ocean floor for carrion, its long limbs moving with unsettling grace. To protect themselves from predators, the smaller or younger crabs will sometimes decorate their shells, creating camouflage from things like kelp.

Despite its intimidating form, it’s a gentle scavenger — and a vulnerable one. They lose legs easily. And despite being one of the creepiest animals in the world, the species has long been harvested for food, and because it reproduces slowly, overfishing can quickly reduce populations. Sustainable fishing practices are now being encouraged by Japanese marine agencies to ensure this ancient survivor doesn’t vanish into legend.

Few arthropods have been as misunderstood as the camel spider, a creature that looks terrifying enough without the help of urban legend. Despite their name, they’re not spiders at all, nor scorpions; they belong to their own distinct order: Solifugae. They roam deserts and arid grasslands across Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas, where they hunt insects and small vertebrates with their oversized jaws and lightning-fast speed.

Camel spiders earned their place as one of the scariest animals in the world during the the Second Gulf War, when sensational emails and tabloids turned Solifugae into viral monsters. Stories claimed they could sprint at 25 miles per hour, leap several feet into the air, anesthetize victims with venom, or even devour the stomachs of sleeping camels. None of it is true. Camel spiders are non-venomous, can’t jump, and rarely exceed 10 centimeters in body length. They don’t chase humans — they simply seek shade, which might make them appear to “follow” soldiers in desert camps.

In reality, Solifugae are remarkable survivors, adapted to extreme heat and scarcity. Their speed, silence, and nocturnal habits have earned them a reputation far scarier than their true nature. Misunderstood creatures like these remind us how myths can eclipse the real wonder of the natural world, as well as how quickly fear spreads when science takes a back seat to sensationalism. Often, the scariest animals in the world only make us uncomfortable because we don't understand them.

Standing nearly five feet tall with a bill like a medieval clog, the shoebill looks equal parts dinosaur and statue. It hunts lungfish and frogs in the swamps of central and eastern Africa, holding perfectly still for long stretches before striking with astonishing speed. It's even been known to fight Nile crocodiles to feed on their young.

But the shoebill’s swampy kingdom is vanishing. Wetlands across the Nile Basin and Congo region are being drained for agriculture and settlement, threatening the bird’s food sources and nesting grounds. Conservation groups now monitor populations closely, reminding us that even the strangest and most intimidating creatures depend on the fragile persistence of their habitats.

Despite its dramatic name — it literally means “vampire squid from hell” — this deep-sea cephalopod isn’t a bloodsucker at all. Found in the oxygen-poor, lightless zones of the ocean, it glides through the darkness with webbed arms that resemble a cloak, its enormous blue eyes glowing eerily. When threatened, it can turn itself inside out, revealing spiny appendages and releasing a bioluminescent cloud. Instead of hunting, it feeds on drifting organic debris known as “marine snow,” making it a scavenger of the deep rather than a predator.

The vampire squid is perfectly adapted to survive where few other animals can. But even its dark refuge is not safe from human activity. Deep-sea mining, warming, and acidification threaten the ecosystems that sustain it. Studying species like Vampyroteuthis infernalis gives scientists clues about life in extreme environments, as well as what we stand to lose if we destroy them.

Few animals inspire as much wary admiration as the honey badger. Compact and muscular, it raids beehives, kills venomous snakes, and takes on predators many times its size. Its loose, tough skin allows it to twist and counterattack when bitten, and it doesn’t seem to care about bee stings, porcupine quills, or even bites from cobras.

The IUCN Red List classifies honey badgers as Least Concern, but “least concern” doesn’t mean invulnerable — even if they are tough as nails. And the IUCN notes that honey badger populations are decreasing. Honey badgers are still persecuted by farmers who see them as thieves, and they're also sometimes poisoned indirectly through pest control. In particular, they often come into conflict with beekeepers. Their fearlessness has made them icons of the wild but also targets for humans who see them as a nuisance or danger.

The fangtooth may be small — usually less than six inches long — but it’s a terror to behold. Its jagged teeth are so large they must fit into special sockets in the skull, and its skin is dark and scarred from life in the depths. The fangtooth's teeth are the largest in the ocean proportional to its body size. The species lives thousands of meters below the surface, where the pressure is crushing and light never reaches.

Its monstrous face hides a surprisingly gentle truth: the fangtooth’s tiny size makes it harmless to humans, and its fierce appearance is simply the result of extreme adaptation.

If aliens ever visited Earth, they might look like the star-nosed mole. Its snout is ringed with 22 pink tentacles that wriggle constantly, each packed with sensory cells. In milliseconds, they help the mole locate and eat small invertebrates underground — the fastest foraging speed ever recorded in a mammal. (It even holds an official Guinness World Record for its speedy eating.)

It’s easy to recoil from such strangeness, but this mole is a marvel of wetland ecosystems in the eastern United States and Canada. It thrives in soft, water-rich soils, habitats increasingly threatened by development and drainage. Protecting wetlands protects the mole and the intricate networks of life hidden just beneath our feet.

By day, the potoo remains disguised as a branch, a motionless lump perched on a tree. But when night falls, it opens its enormous yellow eyes and emits a moaning, ghostlike call that echoes through the rainforest canopy. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology describes its "drawn-out moaning growl" as "among the most exciting and perhaps most unsettling nocturnal sounds in the Neotropics." That sound, coupled with its large, dark eyes, always seem to earn it a place on lists of the scariest animals in the world.

These nocturnal birds depend on large tracts of tropical forest across Central and South America. Deforestation not only destroys their nesting sites but also undermines their camouflage — their greatest defense. Preserving rainforests means preserving the delicate chain of oddities that make up the living night.

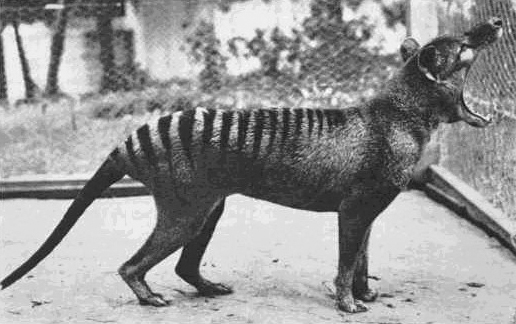

The thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, once roamed the forests of Australia and Tasmania. The thylacine disappeared from New Guinea and mainland Australia roughly 3,600 to 3,200 years ago —well before European arrival — likely due to competition from the newly introduced dingo, which never reached Tasmania. By the time Europeans settled the island, an estimated 5,000 thylacines still roamed its forests.

Seen as a menace to livestock, the species was ruthlessly hunted under government bounties throughout the 1800s. The last known thylacine died in captivity at Hobart Zoo in 1936. Today, it endures as both a cultural icon and a haunting reminder of how quickly human fear can erase an entire species.

Known for its enormous size and fearsome sting, the Asian giant hornet is the world’s largest hornet species. You may have heard this hornet sensationalized in the media as the "murder hornet" after its discovery in North America. Individuals can grow up to five centimeters long, with stingers capable of penetrating protective clothing. In their native habitats across East Asia, they are skilled hunters that decimate entire colonies of honeybees. A few hornets can destroy a hive in a matter of hours by decapitating the bees in what scientists call a "slaughter phase."

The aye-aye of Madagascar might be the strangest primate alive. With giant eyes, bat-like ears, rodent teeth, and a long skeletal finger used to tap on wood and extract grubs, it’s both brilliant and eerie. Its unique foraging method — called “percussive foraging” — is unlike anything else in the primate world.

But local folklore often casts the aye-aye as a harbinger of death, and individuals are sometimes killed on sight. Combined with deforestation across Madagascar, the aye-aye is now endangered. Protecting the aye-aye means not only saving forests, but also changing hearts and minds.

Species within the genus Bathydevius, first described in recent deep-sea surveys, live in the pitch-black trenches of the ocean. With translucent bodies and pale, lidless eyes, they drift through crushing darkness where few lifeforms can survive.

The deep ocean is increasingly threatened by mining and pollution before we even understand what lives there. These “ghost fish” embody both mystery and fragility. They're a living reminder that the scariest thing about the natural world isn’t what we know, but what we could lose before we’ve had a chance to see it.

The scariest animals in the world aren’t monsters. They’re survivors, the products of harsh environments and millions of years of evolution. They remind us that fear and fascination often come from the same place: awe. Our planet is filled with dazzling ecological variety, and protecting the world's biodiversity is the only way to ensure that this wonder endures. Every eerie adaptation and unsettling face tells a story of persistence, proof that life can thrive in the most extreme and unexpected forms. By safeguarding biodiversity we preserve the imagination, resilience, and mystery that make Earth unlike any other world we know.